EU’s Response to COVID-19 Unveils Division and Fundamental Weakness

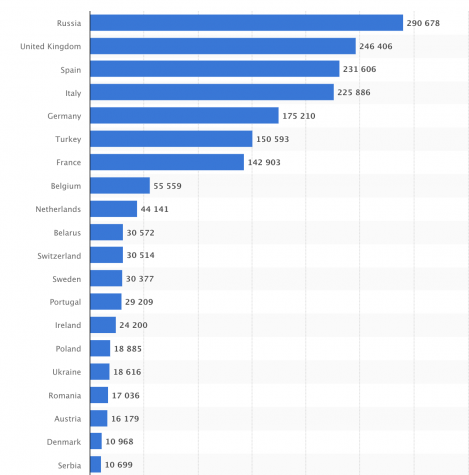

On Jan. 24, only weeks after the novel virus was first reported by Chinese Health officials, France confirmed three cases of coronavirus. From that point on, coronavirus (COVID-19) would ravage its way through Europe. As of May 19, there have been roughly 1.8 million confirmed cases in Europe, which constitutes importantly 40% of the total global number of cases. The devastation of Europe, especially countries like Spain and Italy who were hit particularly hard, demonstrates the failure of the EU to act multilaterally to prepare and protect member states.

At the advent of the COVID-19 outbreak, European leaders did not expect the magnitude of the impact of the disease.

“I think it is only honest to admit that nobody expected that the dimensions of this outbreak would be such here in Europe,” Janez Lenarčič, the EU’s commissioner for crisis management, said in a POLITICO interview. “Why? Because some previous experiences perhaps made people believe that this would not be so, so huge. For instance, SARS, if you remember, or MERS, or even Ebola — all of these previous outbreaks were either localized or they died out before they spread all over the world like this one.”

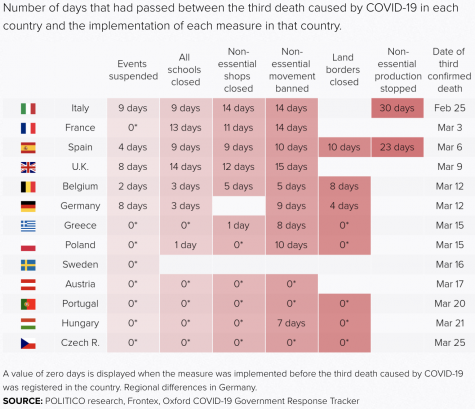

Fearing an overreaction would cause unnecessary panic, European leaders were lulled into inaction. When the first cases of COVID-19 in Europe were diagnosed, public health officials were well aware that the disease was circulating in Europe. Nevertheless, the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) was secure in the fact that EU countries were well-prepared to identify cases and treat patients. This unearned sense of confidence among the EU resulted in many European nations waiting too long to implement quarantine measures.

The complacency of the EU in the early days of the European outbreak resulted in the organization falling behind at every step of their COVID-19 response, including testing capacity and obtaining medical supplies. On April 7, Mauro Ferrari, EU’s chief scientist, resigned from his post. In a statement by the European Research Council (ERC), it was revealed the resignation was for reasons not connected to COVID-19. However, Ferrari described the frustration he felt when working with the ERC to develop response to COVID-19 in a statement to the Financial Times.

“I have been extremely disappointed by the European response to Covid-19,” Ferrari stated. Ferrari delineated many grievances he had with the ERC, including “recurrent opposition to cohesive financial support initiatives” and “the marginal scale of synergistic scientific initiatives.”

Not only was the EU behind on its response to COVID-19 but the organization faced political obstacles as well. While the EU does have the authority to acquire medicine and equipment for member states, it has no means to enforce a coordinated course of action regarding healthcare policy.

With the threat of a pandemic looming, states were more concerned with closing borders and competing over supplies than cooperation and collective action among member states.

“From day one, the EU was fighting an uphill struggle, as it rushed to piece together a pan-European response to a healthcare crisis with no real authority to do so,” says Andrea Renda, a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Policy Studies. “It was trying to force nations that didn’t trust one another to work together on procuring and stockpiling medical supplies at the same time they were unilaterally closing their borders.”

The lack of urgency from the EU amidst the global pandemic has caused widespread dissatisfaction among Europeans, especially in the countries most negatively affected. For instance, 88% of Italians believe that the EU failed their country according to the Monitor Italia survey.

The COVID-19 pandemic is revealing another weakness of the EU: the disparity between wealthier and poorer nations. Wealthy European countries that contribute heavily to the organization are not apt to subsidizing less wealthy nations. Correspondingly, the less wealthy nations take offense at the power wealthy nations can wield in times of crisis. These factors undermine the cooperative spirit necessary to take effective action against a rapid moving crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Europe has begun the process of lifting quarantine measures. Back in April, Denmark became the first country in Europe to start reopening its schools. At the same time, Austria, Italy and Spain have allowed certain businesses to reopen and some non-essential workers to go back to their jobs. Many other countries, such as France, Norway, and Germany, have outlined and begun implementing plans to reopen businesses and schools.